So What, Who Cares (vol 3, issue 8) Who wants to know why the Chelsea Hotel was a big deal?

Hello!

I have to be honest: I was all set to write tonight, and then my daughter asked me to hold her while she fell asleep, and 30 minutes later, I woke up curled around a snoring kindergartener and the thought that sometimes, the best way to end a week is to take the hint the universe is sending you.

So with that, please enjoy a big ol' chunk of fun pop culture for the weekend. I'll be back [yawn] with a full edition on Monday.

Your pop culture moment of the day: In a lovely moment of pop culture synchronicity, last year I ended up checking Patti Smith's Just Kids out of the library right as I TiFaux'd the HBO documentary Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures. The book's a quick, one-afternoon read -- perfect if you have a porch and a bottomless drink -- and the documentary is fine if no small children are about. In fact, I highly recommend the documentary because it's quite fun watching art curators look at a picture of a man having a moment with a bullwhip, then murmur about chiaroscuro.

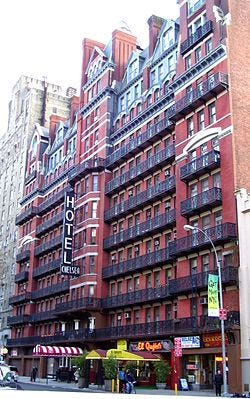

The Chelsea Hotel figures as a character in both the book and the documentary, and so I was a goner this week when I read "Make American Bohemian Again," an essay that asks why there aren't more art colonies like the one the Chelsea was.

This essay reminds me of a passage in William Gibson's All Tomorrow's Parties, where a main character talks about the perils of accelerated cultural churn:

“Bohemias. Alternative subcultures. They were a crucial aspect of industrial civilization in the two previous centuries. They were where industrial civilization went to dream. A sort of unconscious R&D, exploring alternate societal strategies. Each one would have a dress code, characteristic forms of artistic expression, a substance or substances of choice, and a set of sexual values at odds with those of the culture at large. And they did, frequently, have locales with which they became associated. But they became extinct.”

“Extinct?”

“We started picking them before they could ripen. A certain crucial growing period was lost, as marketing evolved and the mechanisms of recommodification became quicker, more rapacious. Authentic subcultures required backwaters, and time, and there are no more backwaters. They went the way of Geography in general. Autonomous zones do offer a certain insulation from the monoculture, but they seem not to lend themselves to re-commodification, not in the same way. We don’t know why exactly.”

When there are no more dreamtimes for civilization, where do the next dispatches from the outskirts of human potential come from?

For more on Mapplethorpe, romp through the archives of Vanity Fair: Bruce Weber and Ingrid Sischy talk about the photographer's legacy; Dominick Dunne dishes on Mapplethorpe's final months with AIDS; former Interview editor Bob Colacello recalls his association with the photographer in the 1970s; and critic Mark Stevens' makes a turn-of-the-1980s assessment of Mapplethorpe's work, "The Shock of the Faux."

*

FOOTER TEXT, BECAUSE THIS IS THE END OF THE EMAIL: Thank you all for reading! It is delightful to know you're all out there -- now add to the army of readers by telling your pals to subscribe! Talk to me via Twitter because I love hearing from you. And I have at last noticed that you can send me email via TinyLetter, so I'll finally answer those emails! What a time it is to be alive.