So What, Who Cares (vol 3, issue 10) Why economists have started noticing women who aren't working

Hello!

I find that New Yorker profiles can be hit or miss lately -- neither the Ali Wong nor Mo Willems ones told me anything new, and it's not like I majored in Knuffle Bunny and minored in Baby Cobra -- but this profile of Dr. Carla Hayden, the first black woman to be the Librarian of Congress, is a worthwhile read.

This is a woman who's vigilant about American privacy rights, who speaks passionately about libraries as the beating hearts of diverse communities, who lives to serve. In a more just and creative world, we'd see her in the next Avengers line-up, using Captain America and Thor as shelving clerks.

*

Female unemployment is finally getting some attention. There have been a spate of stories over the past decade about the rise in unemployment among men in "prime working years" and a search for explanations including, but not limited to, a decline in manufacturing work and construction jobs, and white men's refusal to work in caregiving jobs because those are for women.

However, people are finally noticing that "prime" (i.e. ages 25-54) women's participation in the workforce has been dropping too. Although several of the same factors that depress male participation are present -- a decline in manufacturing, volatile retail and construction work cycles, etc. -- there's another biggie researchers have identified: Caregiving, either for elderly relatives or for young children.

In every state in the union, child care eats up at least 31% of a minimum wage earner's take-home page. Child care costs have risen 25% over the last decade, even as wages have remained mostly stagnant for both child care workers and child care customers. And when women look at how much more complicated their lives are going to be when they're racing against the clock at both work and daycare drop-off or pick-up, then see exactly how little money they'll get for all that extra hassle ... that's when they leave

So what? The shrinking of American women's participation in the workforce is exactly the opposite of what's happening in nearly every other industrialized country. A smaller female workforce has repercussions on a macro level -- for one thing, that's a smaller total workforce, and if you have a smaller workforce, that's fewer taxpayers to keep the lights on at a local or federal level.

Who cares? People who enjoy roads, standing armies, public schools or postal services. People who know that when women work, it usually boosts a network of extended family via family wealth-building and educational opportunities. And maybe even people who are eyeballing the increasing number of links between long-term economic health and government policies that don't seem to punish people for having families.

(A recent National Bureau of Economic Research study contrasted Canada's women workforce participation against the U.S. and concluded that Canadian women's much higher labor participation rate was the result of government policies, among them a year of paid parental leave and subsidized daycare.)

Women's workplace participation would likely rise if the U.S. had paid leave policies in place on a federal level. There is research showing that women are more likely to return to work if they've had paid parental leave; the Resolution Foundation estimates that 3.3 million more American women would be in the workforce if the U.S. had similar parental leave benefits to the U.K., and the Financial Times notes:

The average length of paid leave available to mothers across the OECD countries has increased from 17 weeks in 1970 to just over a year. In the US, it was zero in 1970 and remains zero to this day.

In 1990, the United States had the sixth-highest female labor force participation rate amongst 22 high-income OECD countries. By 2010, its rank had fallen to 17th. Start placing bets on whether we'll slide to 22 in this decade.

*

Your pop culture moment of the day: I just finished reading Linda Przybyszewski's The Lost Art of Dress: The Women Who Once Made America Stylish, a book about the rigorously-trained, earnest-minded domestic science professionals who taught generations of women how to plan for, sew and grow beautiful wardrobes on realistic budgets. Przybyszewski is a historian by training, and her careful work outlining the rise and fall of the "dress doctors" and the very real impact of domestic science on women's lives across all socioeconomic strata of the U.S. is a delight. I also enjoy how cranky Przybyszewski is about most of today's clothing, retail as a hobby, and modern women's magazines.

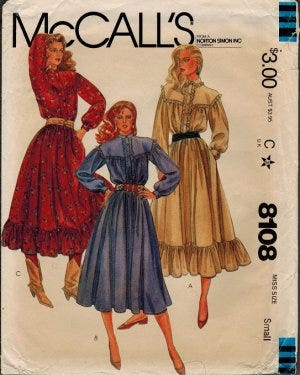

The book also made me even more grateful for the McCall Pattern Company's Instagram, which is a lovely mix of modern projects and throwback patterns. For more on how McCall has found a way to capture the DIY spirit of this decade, read this excellent New York Times article, "Do-It-Yourself Fashion Thrives at the McCall Pattern Company."

The Lost Art of Dress also prompted a nice afternoon think on the undeniable connection between the physical sensation of our clothing and its effect of our state of mind. So imagine my delight when I read Isabel B. Slone's "Prairie Dresses Help Me Feel Like Myself," an article devoted to the delight of skipping the simple, boxy shapes of normcore in favor of Girl Gone Gunne Sax. Sloane's essay feels like a portent of a sartorial shift to come.

I have noticed a determined effort on the part of retailers to try and push something, anything, on recalcitrant American women to make them reboot their wardrobes. (Last Sunday's T magazine is a dream of 1980s maximalism and shoulder pads, an utterly unsurprising development given current events.) But in retail moment were every purchase seems like an opportunity to make a statement, what will consumers do with an aesthetic that references a time when women couldn't vote and minorities had few to no civic rights?

*